This week we read about position and outcomes statements for the teaching of writing. These position statements help define our expectations and ideas surrounding the teaching of writing. We also read about professional associations in our field of study: CCCC (Conference on College Composition and Communication, and WPA (Writing Program Administrators).

As a communications freelancer, I have had the opportunity to work as a resource development contractor curating grant opportunities for nonprofits addressing early literacy issues. I’ve always been aware that the NCTE (National Council of Teachers of English) is devoted to improving the teaching and learning of English and the language arts, offering grant programs funding research related to underrepresented populations, equity pedagogies, curriculum changes, and the effect these changes have on students, changes in teaching methods, student interaction and learning, community literacy, and other relevant subjects (PND, February).

It’s fascinating to learn about the Conference on College Composition and Communication (CCCC) and the many other resources the NCTE offers in our field of study.

“The CCCC advocates for broad and evolving definitions of literacy, communication, rhetoric, and writing (including multimodal discourse, digital communication, and diverse language practices) that emphasize these activities’ value to empower individuals and communities” (n.d.).

The CCCC is committed to supporting diverse communicators inside and outside of postsecondary classrooms. “To this end, among other things, the CCCC and its members develop evidence- and practice-based position statements for those invested in language, literacy, communication, rhetoric, and writing at the postsecondary level” (n.d.).

Some of the position statements I will prioritize in my classroom are:

I will advocate for equitable access to and accessibility of texts, tools, and information by seeking out free high-quality digital course materials in my classroom. I would hate for the cost of a book or some other learning resource to create a boundary for any students.

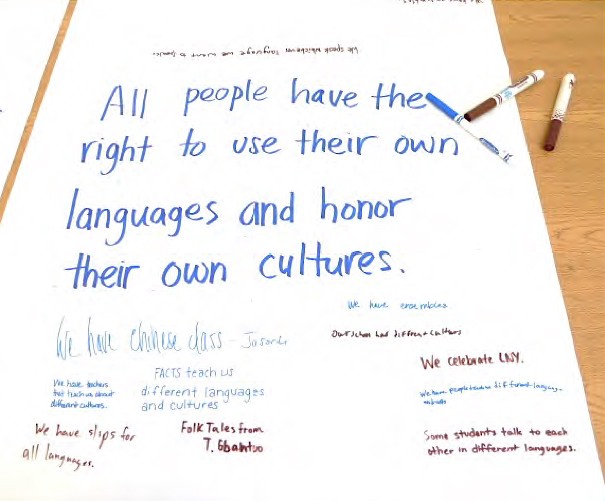

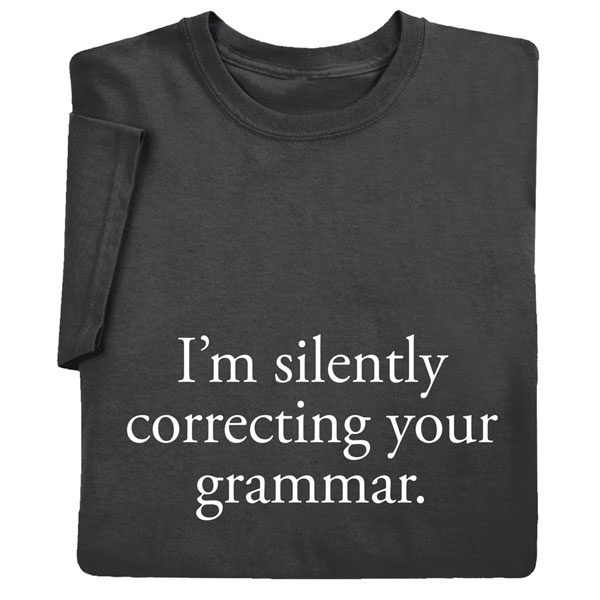

Building on Students’ Right to Their Own Language, I will pay close attention to my assessment practices, prioritizing authentic rhetorical choices over grammatical and stylistic errors or linguistic differences. I agree with, Principles for Assessment in those assessments that are keyed closely to an American cultural context may disadvantage second language writers and students whose home dialect is not the dominant dialect.

I will not be a stickler for grammar. I will avoid a grammar practice that hinders the development of students’ oral and written language, focuses my teaching methodology on the Principles of Sound Writing Instruction, emphasizing the rhetorical nature of writing.

The position statements provided by the CCCC are perfect for offsetting the potential for “expert blind spots.”

Authors Mitchell J. Nathan and Anthony Petrosino define the ‘expert blind spot’ hypothesis as the claim that educators with advanced subject-matter knowledge of a scholarly discipline tend to use the powerful organizing principles, formalisms, and methods of analysis that serve as the foundation of that discipline as guiding principles for the students’ conceptual development and instruction, rather than being guided by knowledge of the learning needs and developmental profiles of novices.” Do you believe in the ‘expert bling spot’ hypothesis?

Works Cited

“Definition of Literacy in a Digital Age.” National Council of Teachers of English, NCTE, 7 Nov. 2019, ncte.org/statement/nctes-definition-literacy-digital-age/.

“NCTE – Home Page.” NCTE, ncte.org/.

“Principles for the Postsecondary Teaching of Writing.” Conference on College Composition and Communication, 21 July 2018, cccc.ncte.org/cccc/resources/positions/postsecondarywriting#principle5.

“Resolution on Grammar Exercises to Teach Speaking and Writing.” National Council of Teachers of English, 30 Nov. 1985, ncte.org/statement/grammarexercises/.

“Welcome to the CCCC Website!” Conference on College Composition and Communication, cccc.ncte.org/.